By Jeff Hampton

(Suggested by actual events)

“Come on Patty, let’s go,” said Dorothy, shouting down the hallway at her always-dawdling daughter. “You said you wanted to see Elvis, and it’s not going to happen if you don’t get moving.”

“Oh, Mother, I wish you’d quit talking that way,” she huffed loudly from her room. “You know it’s YOU who wants to see Elvis. I couldn’t care less.”

“But we talked about . . . .”

“No, Mother,” Patty interrupted as she came into the den, “YOU talked about it, and YOU’ve been talking about it for a week. You’ve been up and down the street telling the neighbors, ‘I’m taking Patty to see Elvis Presley,’ but we both know you’re really just taking yourself and you’re dragging me along.”

Patty stood in the middle of the den and stared at her 31-year-old mother who was trying her best to look 20.

“Don’t be so smart,” said Dorothy. “We’re both going and that’s that.”

She leaned toward the mirror, checked her hair one last time, and grabbed her purse off the hall table. George was working late again and, declaring that morning that he had no interest in “rockabilly” music or whatever they were calling it, he told his girls to have a good time and he’d have the lights on when they got home.

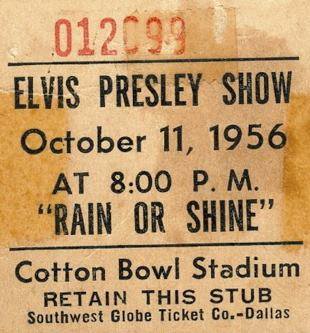

It was October 11, 1956, and the evening air was cool and just right for an outside show at the Cotton Bowl Stadium. Fair time in Dallas always brought uncertain weather: Warm and sunny one day, cool and rainy the next. Dorothy had already bought the tickets that had “Rain or Shine” stamped on them, so she was glad that “shine” was the forecast for the evening.

Dorothy backed the Chevy down the driveway and onto the street, clunked the shift into drive and started the short trip from their East Dallas neighborhood to the fairgrounds. They could have taken the bus or the streetcar, but when Dorothy said she didn’t want to ride with a bunch of strangers so late after the show, George gave her the keys and caught a bus downtown to the bank.

A red light stopped them on Gaston Avenue, and Dorothy took the opportunity to check herself again in the rearview mirror. The brooding 12-year-old sitting beside her did not change the fact that Dorothy was still young and pretty. She and George had married right after high school and Patty arrived just 10 months later. They were still very much in love and George was still attentive, but she thought the job at the bank had chipped away at some of his boyish playfulness.

The light turned green and they were on the move again. A few minutes later they were being directed to a parking spot by a man with a red flag. The second they opened the car doors, Dorothy and Patty could hear the shouts of the Midway hawkers and could smell the mingling aromas of corny dogs, cotton candy and popcorn. Dorothy looked over at Patty and saw the hint of a smile invading her face. “Finally, she’s loosening up a little,” Dorothy thought. She worried that her daughter was far too serious and focused for her age.

“Don’t hold my hand,” Patty said in a pre-emptive whisper to her mother as they started to merge with others walking toward the gate.

“But I wasn’t going . . .,” Dorothy started to say, but Patty interrupted: “I promise not to get lost or kidnapped.”

Dorothy restrained herself by clasping her hands together, although she did place her hands on Patty’s shoulders as they squeezed down into a single file to go through the gate and into the fairgrounds. Once past the gate, the crowd spread out again and Dorothy let go of Patty and stepped up to walk side-by-side.

“We have an hour before the show,” Dorothy said, looking at her watch. “What do you want to see?”

“Oh, nothing in particular. I suppose we could go check out the ‘57 models.”

“No, we’re not in the market for a new car this year,” said Dorothy. “We’ll see them on the streets soon enough.”

“Then let’s go to the Women’s Building.”

Dorothy was relieved. Her daughter was showing tomboy tendencies, but cars? That was just plain scary. Cooking was something she’d need to know how to do some day.

What Dorothy didn’t know was that her daughter believed it was she who still needed help in the kitchen. It wasn’t that Dorothy was a bad cook; she did fine on the basics. But she was a restless and distracted cook, and her attempts at new recipes and techniques often brought disaster. George and Patty always gave her high marks for trying, and thanks to her flare-ups they were the first family on the block with a home fire extinguisher. George brought it home one day and rather than being embarrassed, Dorothy was happy to brag to the neighbors about this latest household convenience. “Great to have around if the car catches fire or a bulb pops on the Christmas tree,” she said.

They meandered up and down the aisles of the pavilion, inspecting the latest products and stopping to catch bits and pieces of demonstrations. If one was ending, Dorothy would race up to the front for a free sample. “Eat up,” she said to Patty. “This is supper for now.” Before they stepped out into the cool air they paid their respects to the winners of the annual competitions – everything from pickles and peaches to paintings and quilts.

And then it was time to go to the stadium. It was a package show – 60 minutes of various performers of limited name recognition and then Elvis Presley, who Variety magazine just that month had dubbed “the king of rock and roll.” Dallas was the first stop on a four-day tour that would include Waco, Houston and San Antonio. Ticket sales had already topped 26,000, making it the largest show crowd in the city’s history, and by the time Dorothy and Patty entered the stadium it looked like they were the only two of the 26,000 who hadn’t found a seat.

Patty snickered through her nose when she saw the look of shock and disappointment on her mother’s face. “Oh, stop it,” Dorothy snapped. “This is perfect. We can see better from the higher seats anyway.”

They climbed and climbed and by the time they reached the empty seats the first act was already performing.

“Who’s that,” Patty shouted over the loud music with a touch of sarcasm that meant “is this someone I’m supposed to be impressed with?”

Dorothy just shrugged and nobody near them answered either because nobody seemed to be paying attention. They’d all come to see Elvis, and when singer after singer took a bow and left the stage, the applause was polite but not especially enthusiastic. While Patty sat with her chin in her hands, Dorothy surveyed the crowd. The majority were teenagers, and among them, mostly girls. If there were boys in the crowd, they were only there because their girlfriends were there.

Another act came and went and the audience was buzzing with impatience when a hush began to sweep down the stands from an upper corner. Dorothy and Patty both noticed the change, and Patty sat up straight and saw people pointing to the far corner of the stadium. She leaned sideways to see a bright red convertible slowly emerging from the shadows of the tunnel with a driver and a passenger in the front seat. She couldn’t make out who it was as the car made a big loop around the back of the stage, but when it came around to the front she saw the jet black hair and long sideburns.

“That’s him,” Patty said with a whispered excitement to nobody in particular.

The crowd became hushed as Elvis got out of the car, but then they went wild when he shook back his head, laughed, and leapt onto the stage. And for the next half hour it was pandemonium as the new “king” crooned and wailed through one hit after another.

Somewhere between “Love Me Tender” and “Hound Dog” Patty awakened. It happened slowly, first with a toe tap, and then a knee shake, and then a head bob to the rhythm of the music. With each new song, she sat taller in her seat, then on the edge, and then she was standing. With her hands stretching upward like a sunflower reaching for the light, she joined the swaying rows of screaming, crazed teens.

“Isn’t he dreamy!” she shouted over her shoulder, but Dorothy didn’t answer. She wasn’t hearing anything. It was as if someone had turned the volume down on a television set. She could see Elvis gyrating on the stage and the young people jumping up and down with every dip and grind of his hips, but she couldn’t hear anything. The electricity that flowed from the stage and into the crowd hadn’t touched her. There wasn’t a connection – not like the one she felt a dozen years earlier when Sinatra came to town.

Dorothy looked sideways down the row and caught the glance of another woman sitting in the shadow of her swooning daughter. She turned back toward the stage, aware now of two things: She was no longer 20, and Patty was no longer a little girl.

THE END

Copyright © Jeff Hampton 2010